Why the Oscar for Best Picture is Harder to Predict than Ever

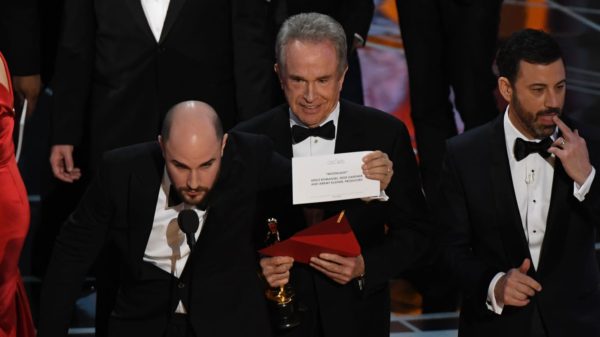

It gets even more painful re-watching last year’s infamous Best Picture blunder when you know what’s coming – the confident, pretty mass of white people who made “La La Land” strolling up to the stage and hugging each other, the commotion as something doesn’t seem right, and the confusion as one of the film’s producers tries to bury his frustration and disappoint as he informs everyone that “Moonlight” is the actual winner. It was like Toto pulled the curtain on the Wizard of Oscars.

But as a film and Academy Awards nerd of sorts, the problem I saw had nothing to do with a star-struck backstage employee handing off the wrong envelope.

I was more fixated on why “Moonlight” director Barry Jenkins didn’t win Best Director, or conversely, why Damien Chazelle was named Best Director and his film, nominated for a record-tying 14 Oscars, didn’t win the Best Picture.

The Academy Award for Best Picture has slowly taken on a life of its own, and anyone who confidently thinks they know who’ll win it in 2018 is a fraud. All the usual tell-tale signs collapsed in on themselves when “Moonlight” pulled the upset last year in the very definition of theatrical fashion. And with a diverse crop of nominees this year and little consensus around the year’s best film, anything seems possible.

I thought I’d explore this change, and in doing so I’ve come to realize how unsurprising “Moonlight’s” win really was, and what it can tell us about who is more likely to win – or not win – film’s most coveted prize on Sunday.

The Best Picture Monster

The week before the Oscars, Vox published a video explaining why “safe movies” like “La La Land” were a shoo-in for Best Picture, whereas bolder films such as “Moonlight” were left in the dust. They were wrong, but they were looking at the right data. The answer lies in the way voting for Best Picture has changed since 2009.

That year, the Academy expanded the Best Picture category to 10 films (and two years later revised it to “as many as 10” films), in an effort to celebrate more films – and allow more studios to leverage the phrase “Oscar nominee for Best Picture” to sell tickets. But with more choices came the need for a different voting system.

Rather than select only their favorite film, voters now rank their preferences. The vote-counters then tally the first place votes, and eliminate the film with the fewest votes. Of those ballots whose first choice was eliminated, their vote instead goes to their second-ranked film, and the process continues until one movie receives 50% plus one of the votes. (Confused? Just watch this video)

Vox asserts this instant runoff process favors “safe” movies that are not usually people’s top choices but tend to finish higher up in consensus rankings like these. They argue that’s why films about show business have won Best Picture a lot in recent years (e.g. “Birdman,” “Argo,” “The Artist”); they’re bound to be in the top half of Academy voters’ ballots. Because “La La Land” was more generally liked, safe and about Hollywood, Vox saw no way for it to lose.

Vox wasn’t wrong to predict “La La Land” would win; they were wrong when they categorized it as safe and generally liked.

Personally, I really liked “La La Land,” but felt “Moonlight” was the better film. My impression has been that many if not most people who’ve seen both would agree. So even though “Moonlight” is a “bolder film” in its approach and subject matter, it’s actually more of a consensus choice. For example, as a regular listener of the Filmspotting podcast, I noticed that on the year-end Top 10 episode, “Moonlight” was the only movie to make all four critics’ lists. I don’t think that was an exceptional occurrence.

“La La Land,” on the other hand, made two of the four lists. And in general, it had as many people who hated it as who thought it was the best movie of the year. In talking with friends and family, I heard many people voice outward dislike toward it, or post on social media asking what all the hype was about. No one had anything bad or indifferent to say about “Moonlight.”

The bold choice is actually “La La Land” in the Vox scenario; we were just led to believe it was obvious and safe given the awards piled on it in the two months leading up to the Academy Awards.

So it’s easy to imagine a scenario in which “La La Land” received the most first place votes in the first round of vote-tallying given how much the Hollywood populace that largely comprises the 6,000 Academy voters seemed to love it, but lost ground in subsequent rounds as more second and third place votes went to “Moonlight.”

Looking at this year, “The Shape of Water” comes in with the same momentum as “La La Land,” with wins at the Golden Globes and the Producers Guild Awards. The difference is that most people have good things to say about this film. On the other hand, “Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri” won big at the Screen Actors Guild Awards and BAFTAs and could well win a couple acting Oscars. That film, however, has been extremely divisive, and it strikes me as unlikely that it would achieve 50 percent of the votes plus one.

Call this the opposite of a bold prediction, but I will hang my hate on “Three Billboards” not winning Best Picture. Whether “The Shape of Water” can hold off people’s choice picks like “Get Out,” “Lady Bird” and even “Call Me By Your Name” is tough to guess.

Best Director and Best Picture: The Great Divide

The same voting body that anointed “Moonlight” the Best Picture last year, ultimately chose Damien Chazelle as the best director of the year. In theory, if you thought that Chazelle was the best director, wouldn’t you vote for “La La Land” for Best Picture?

There is a large school of thought among film buffs called auteur theory, or the idea that the director is the author of a film and therefore the linchpin of its success. That notion has long guided the Academy Awards. Only in 25 out of the 89 years since the Academy Awards began has Best Director and Best Picture not lined up. In just the last five years, that split has happened four times.

Year – Best Picture – Best Director

2017 – Moonlight – Damien Chazelle for “La La Land”

2016 – Spotlight – Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu for “The Revenant”

2015 – Birdman – Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu for “Birdman”

2014 – 12 Years a Slave – Alfonso Cuaron for “Gravity”

2013 – Argo – Ang Lee for “Life of Pi”

Going back to the start of instant runoff voting, that’s four splits in nine years. There were only four splits in the 23 previous years. If you look at all the 25 splits, 13 of them took place before 1956, i.e. the first 29 years of the award (a 45% occurrence rate), while the other 12 took place over the next 60 (a 20% occurrence rate). Take out those four out of the last five, and only eight splits occurred between 1957 and 2012 (about 14.5%).

It’s enough to suggest a major shift has occurred, rather than a closely concentrated anomaly. The question is how much of it is due to the voting process, and how much of it is due to the mindset of voters.

Like all the other categories other than the big one, Best Director doesn’t use a runoff voting system. It’s one vote per customer. These are two fundamentally different ways of counting votes and naming a winner. The Best Picture model favors consensus; the Best Director model (and for all other categories) favors first-place votes.

Voters get more choices in the Best Picture category and they get to rank all the films rather than choosing just one. The odds are greater that your favorite film of the year is represented in the Best Picture category and you can vote for it, but less so that your favorite directing achievement is among the five nominees.

Let’s use this year’s films to make this point. Your favorite film of 2017 might be “The Post.” Because of the nine-film slate, you have the opportunity to vote for “The Post” for Best Picture. (It’s safe to assume given how few awards “The Post” has won this year, that it would not have been nominated if only five spots were open).

If you subscribe to auteur theory, and believe Steven Spielberg should be Best Director, you’re out of luck, because he’s not nominated. So maybe you prefer Martin McDonagh (“Three Billboards”), who directed your #2 Best Picture choice. Well, he’s not nominated either. Since there are only five Best Director choices to nine Best Picture choices, the odds are much lower that your favorite directing job of the year is represented. So, of who is on the ballot, you might vote for 2018 frontrunner Guillermo del Toro even though “The Shape of Water” could be as low as fifth on your ranking of the Best Picture nominees.

Yes, odds are if you like del Toro as Best Director that “The Shape of Water” is going to be higher than fifth in your Best Picture rankings, but you can see the ways in which greater divergence is possible than ever before.

What this means for 2018

The Best Picture-Best Director divide also means that perhaps the even more dependable factor when calculating a film’s Best Picture chances could be next on the chopping block.

I haven’t done the research in a while, but either no film or no more than one or two films (in the last few decades at least) has won Best Picture without at least a Best Screenplay or Best Director win. To at least look at recent history, of those four Best Picture winners who didn’t win an Oscar for their director, all of them won a screenplay Oscar.

Using that rule, every film except for “The Post” and “Darkest Hour” has a fighting chance at beating “The Shape of Water.” The screenplay frontrunners are currently James Ivory for “Call Me by Your Name” and Jordan Peele for “Get Out.” One of the most beloved films of the year, is it possible a horror-comedy could be in position to pull an upset for Best Picture?

A few years ago, at least before the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, I would’ve laughed hysterically at the idea that a stingy, white, male voting body with a tendency toward awarding veteran-helmed prestige dramas would ever award a film like “Get Out.” I still feel as though there’s no way a genre film like this gets called to the stage (on purpose) at the end of the night on Sunday, but if any film is lurking on that nine-film Best Picture ballot, a film that a lot of people loved and admired this year, it’s “Get Out.” No film better captured the zeitgeist of 2017 than that film did.

That said, “Lady Bird” was another extremely popular film. Greta Gerwig could narrowly lose the screenplay award, but perhaps the film is in position to collect those second, third and fourth place votes from voters whose top choices get eliminated in the runoff.

By not making enough enemies, however, “The Shape of Water” may avoid an upset, and we could be sitting here Monday beginning to wonder if the Oscars have become predictable once again. But if the rules of Best Picture stay the same, we’re only another year away from the next big Oscar night surprise.

0 Comments

You can be the first one to leave a comment.