My thoughts on the Inception ending

So it seems that everyone’s talking about “Inception” these days, and yes, it’s for good reason. The film is a towering achievement of creativity/originality and provides some challenging thoughts about our dreams and subconsciouses. Plus, as you can tell by the title of this post, it provides a brilliant closing shot just to make sure everyone leaves the theater talking.

If I need to tell you not to read any further if you haven’t seen the film because “here be spoilers,” then you’re a particularly clueless human being a.) because obviously I’m about to talk about the end of a movie you haven’t seen and b.) you should be out seeing it right now. If you haven’t had a meaningful film discussion since “Avatar” you need to go see this movie. That’s mainly because “Avatar” doesn’t provide any meaningful film discussion. Hence, I’ve just duped you into realizing you haven’t seen a seriously intellectual film in a long time.

So, on to the ending of “Inception” for those of you who go see a good movie when you’re told. Thank you. As for the idiots still reading, you were warned.

Most people love to overanalyze a film that has an ending like “Inception.” If that’s not the right word, then they clamor for an answer. There is no answer, that’s the point. The idea is to encourage discourse on the matter, which is why I’m writing this and many other major sites and blogs have done so before me — and why you’re reading what I have to say about it.

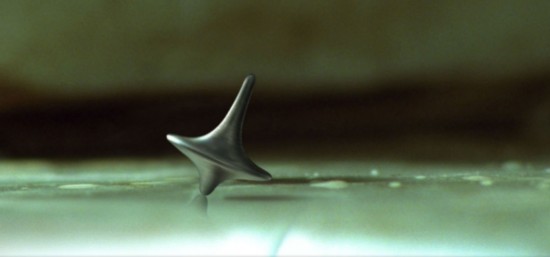

It’s what we call an open ending. Cobb’s spinning top faltering but not falling as the screen goes black sets up a dichotomy that most of us can’t stand, but I love it. If you think that Christopher Nolan knows the answer or that he’s got a sequel in mind revolving around it, well then I’m glad you’re reading because you will learn something today.

Sure, the ending is frustrating because everything seemed so clear in the final moments of the film and most mind-benders never end that way, but then suddenly the wrench comes down (or does it? … ) and we’re left with some juicy ambiguity that makes us doubt ourselves and we all know how much we hate to doubt ourselves about a film, especially when we think we’ve got it.

Just a refresher, the spinning top is Cobb’s totem, an item that only he knows the weight and feel of so that he can tell if he’s in a dream or not. In dreams, the top spins continuously and never falls, but in reality, gravity takes over like it’s supposed to. So, when all the action is resolved and Cobb appears to have made it into the states, reunited with his children and then spins the top right as he leaves to see their faces, when we’re cut off from seeing whether the top would keep spinning or not, we’re stuck wondering whether maybe this happy ending was all a dream … or maybe it was going to fall eventually.

As a creator of a few stories with some ambiguous aspects myself, when I put in something like this, I like to do what most artists do and Nolan probably did: leave it open to interpretation and not force an answer. This is not the artist’s cop out (certainly not for Nolan, he didn’t have to do this), it’s his way of challenging himself with his own art. If the artist can’t debate the answer within himself, e can’t expect anyone to feel the need to discuss it.

So the answer to the spinning top riddle is simply this: it doesn’t matter. The answer to all these conundrums is always “it doesn’t matter.” The question becomes about “why” it does not matter. Naturally that was what I challenge myself to answer after walking out of “Inception.”

To point the question more, why doesn’t it matter if Cobb was dreaming or it was all reality? My thought is that he’s happy either way; he got what he wanted. By virtue of him leaving the scene and seeing his children before ever checking to see if the top would fall proves that it did not matter to him either, so we should get over it.

Think back to the scenes with Cobb and his wife Mal (Marion Cotillard) in his subconscious world that they created to live together to spend a lifetime in dream time what would only be a short time in reality. Cobb had to implant the idea for Mal to want to kill herself in the dream world so they could both live in reality together (and be young again since they grew old in the dream). This was because Cobb wanted to stop living a lie, or whatever the reason, his ultimate desire would not be satisfied by the dream world. After his mistake led to Mal’s death, going back to live with her in his subconscious mind like “she” had been begging of him to do was not what he wanted or he could’ve done it, no problem. Instead, his ultimate desire rested in seeing his children’s faces again. Defeating her (aka actually defeating his subconscious desire to be with her again) was his realization of what was more important. So even if being reunited with his kids was a dream, he finally had achieved his one true goal.

I think what Nolan wants us to see is that even if we are all dreaming right now — each and every one of us actually dreaming this very second — that our happiness is not ultimately contingent on our knowledge of our world being fake or real. The only way we can truly live is to discover what it is we want or need most and strive to achieve it. The imaginary isn’t necessarily any more fulfilling than reality. Our desire to be in one or the other is only a reflection of where we perceive our happiness being.

It seems right and logical to believe that Cobb discovered his children were most important because they were what was real and Mal was gone and he needed to get over it, but by casting some doubt over whether what we thought was real was even real, Nolan reinforces his theme. That, I believe, is him asking us to see happiness as being about our individual perception and as being free of our human fixation over needing to know if something is indeed real or imaginary. Brilliantly, he captures a microcosm of that fixation by exposing it in this last shot of a spinning top because there we are, frustrated and wanting to know whether it was real or all just a dream when the ending to Cobb’s story is peaceful either way.

So there you have it. What do you think? Agree? Disagree?

2 Comments

“Our happiness is not ultimately contingent on our knowledge of our world being fake or real”. I could not have said it better. This is by far the best “explanation” of the film and its ending I’ve read (and I’ve read quite a few). Thank you, Movie Muse.

Ugh! Mooks, you stole the quote I was going to use. Obviously, that’s the part I like Chaitman. Very cool.

Another thought though, not related to the top. I kept noticing that throughout his dreams, he never saw his kids’ faces. At the very end, they turned around and looked at him, and we saw faces. That, to me, told me it was real. Then the whole top/spinning/falling/question added a whole new dimension…